The works of L.E. Threlkeld analysed

- Jeremy Steele

- Jun 8, 2025

- 8 min read

Updated: Jan 31

The somewhat awkward figure of the Rev. L.E. Threlkeld occupied the attentions of Your Amateur Researcher for several years, in connection with the Aboriginal language to the northward of Sydney, Awabakal, also known as the Hunter River-Lake Macquarie language.

Lancelot Edward Threlkeld was born in south London in 1788, and after a chequered start was ordained as a Congregational minister at the age of 27, beginning a career as a missionary. His first posting was to the island of Raiatea, about 200 km northwest of Tahiti in the middle of the Pacific Ocean. By this time he had been married for about nine years. He was to stay in Raiatea for six years. Given his later prodigious efforts in language learning, there is little recorded of any exertions practically at all on his part in this field while on the island. His wife, Martha, died in 1824, which prompted a change in his career direction.

He sailed with his son Joseph later that year, arriving in Sydney with the intention of proceeding back to London, but this was not to happen. The London Missionary Society, his employer, posted him to the settlement in Newcastle, to evangelise the Aborigines there. He eventually arrived at Lake Macquarie in September 1826 after having spent about eighteen months in Newcastle while preparations were being made to establish the mission there.

As was to happen throughout much of Threlkeld’s life, things were to go wrong for him, setting him at odds with the London Missionary Society over the expense incurred in building a house to serve as a mission station and family home. By this time he had married again, to Sarah Arndell, and as well as her and his son Joseph, his three daughters who had been temporarily left in Raiatea, had arrived.

Threlkeld was not the first European settler in the district although he was one of the early ones. There were Aboriginal people about, with whom he soon made contact. It seems that early on he must have formed the idea that the best way for him to make an impact on the local people, and be able to pass on knowledge of Christianity, was to be through coming to terms with the language they spoke. This set him compulsively on a path of writing.

The works of L.E. Threlkeld

Almost immediately he produced his first work, dated September 1825: “The Orthography and Orthoepy of a Dialect of the Aborigines of New South Wales”. This was a 12-page manuscript consisting mostly of sound tables, with a few words and sentences of language. Then, sometime during the following year he worked on and had published in 1827, “Specimens of the Aboriginal Language” (sometimes entitled “Specimens of a Dialect, of the Aborigines of New South Wales”). This was a work of 27 pages, with an attached ‘Circular’ at the end commenting on the book, and on the state of the Aboriginal Mission, as well as on the difficulties Threlkeld was experiencing trying to induce the Aboriginal people to improve themselves.

His next project was much more ambitious. To be able to pass on the Christian message he had determined he needed to translate the gospels, and he began with the gospel of St Luke. This was a major project, which he seems to have begun in 1827, and had definitely completed by 1831 because there is one illuminated manuscript copy of it in the Auckland Library, with an accompanying librarian’s typewritten note: “The Gospel according to St Luke: Aborigine translation. Translated into the language of the Aborigines, located in the vicinity of Hunter’s River, Lake Macquarie &c., New South Wales, in the year 1831 …” There is an addendum: “Threlkeld presented this copy in his own handwriting, with dedicatory notice, to Sir George Grey. A Miss Annie Layard added the illuminations. In 1858 Threlkeld reports that the last survivor of the tribe that spoke this language could be seen, paralytic, on the streets of Sydney, begging alms.”

In around 1828 Threlkeld maintained an exercise book consisting of six pages of handwriting for verbs ending in particular letters, a page of ‘how to say various expressions’, six pages of ‘selections’ (i.e. specimen phrases), four pages on verb moods (indicative, imperative and subjunctive), a double spread of interrogatives and answers, and a final page of a few more example sentences.

Threlkeld’s next literary project, in 1834, was to produce: “A Selection of Prayers for the Morning and Evening from the Service of the Church of England”. There are 52 prayers in the collection, most taken from the Book of Common Prayer, others being Biblical extracts, together with eight whose source could not be identified.

A second major project was to follow: “An Australian Grammar: comprehending the principles and natural rules of the language, as spoken by the Aborigines in the vicinity of Hunter’s River, Lake Macquarie, &c. New South Wales”. This was probably the first grammar to be published of an Australian language. It included sections on pronunciation and orthography, parts of speech (verbs, adverbs, prepositions, conjunctions) as well as a vocabulary and over 400 illustrative sentences.

Next came, in 1836, “An Australian Spelling Book, in the language as Spoken by the Aborigines, in the vicinity of Hunter’s River, Lake Macquarie, New South Wales”. This was a 16-page work consisting of a Key (explanation of the sounds of the vowels), Literi (explanation of the consonants), Word examples, 912 of them, showing hyphenation between syllables, and nine ‘Examples’ from the scriptures, being groups of verses from the gospels. No English equivalents were provided for any of the words or statements.

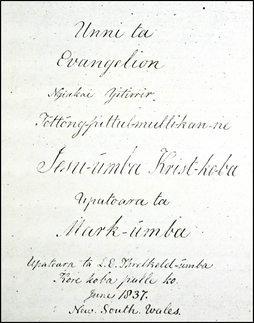

There was more to be done. Having completed his translation of the Gospel of St Luke, on 13 December 1836 Threlkeld began on the “Gospel of St Mark”, completing all sixteen chapters, probably in 1837. Translating the gospels was challenging especially in view of the fact that many things and concepts had no equivalents in the Awabakal language, obliging him to come up with creatively invented translations for them.

The “Gospel by St Matthew” was next. Threlkeld’s Annual Report of the Mission for 1838 stated: “The Gospel of Matthew to the fifth chapter—In Manuscript”. The State Library of New South Wales has a copy of this work, but only up to part-way through the fourth chapter. Threlkeld was to die, on 18 October 1859, before he could complete this work.

Next, completed on 26 November 1850, was “A Key to the structure of the Aboriginal language; being an analysis of the particles used as affixes, to form the various modifications of the verbs; shewing the essential powers, abstract roots, and other peculiarities of the language spoken by the aborigines in the vicinity of Hunter River, Lake Macquarie, etc., New South Wales”. This 83-page work contains a number of general sections, including “Reminiscences of Biraban” (Threlkeld’s principal Aboriginal informant), “Sounds of the tongue of the Aborigines”, and towards the end “Illustrative sentences”, “Selections from the scriptures” and even “The Lord’s Prayers in the language of Tahiti” and elsewhere. Nevertheless most of the Key is an analysis of “the particles”, effectively of suffixes used in the Awabakal language.

Several of the works by Threlkeld featured above were republished in 1892 in a work entitled “An Australian language as spoken by the Awabakal, the people of Awaba or Lake Macquarie (near Newcastle, New South Wales) being an account of their language, traditions and customs by L.E. Threlkeld”, edited by John Fraser. Fraser, born in Scotland nearly fifty years after Threlkeld, was, according to Wikipedia, an ethnologist, linguist and school headmaster, and author of many scholarly works, including the re-presenting of Threlkeld’s writing in this book in 1892.

On p.9 of the Key Threlkeld wrote:

“At the time when my “Australian Grammar” was published in Sydney, in the year 1834, circumstances did not allow me a sufficient opportunity to test the accuracy of the supposition that every sound forms a root, and, consequently, that every character which represents those sounds becomes, likewise, a visible root, so that every letter of the alphabet of the language is in reality a root, conveying an abstract idea of certain prominent powers which are essential to it.*”

About this statement Fraser footnoted:

“*I hope that, in reprinting ‘The Key,’ I shall not be held as supporting this theory.—ED.”

Then, on p.94 of the 1892 book, Fraser introduced another footnote:

“*I have here omitted twelve pages of ‘The Key’; in them our author sets forth his theory that the vowels and consonants of the suffix-forms of verbs and pronouns have each of them a determinate and essential meaning; a portion of this theory appears in the headings of the twenty sections of ‘Illustrative Sentences’ which now follow. These Illustrative Sentences I print for the sake of the examples of analysis which they contain; and yet I do not think that that analysis is in every instance correct.—ED.”

Fraser might not have liked Threlkeld’s analysis but, to Your Amateur Researcher, Threlkeld had identified an aspect of Aboriginal languages that is fundamental to them: suffixes such as -ba, -ma, -la, -ra and the like playing a consistent role in word formation, sometimes with the same function across different languages.

There is, finally, a mystery document found among the Threlkeld papers, a 16-page manuscript beginning with a page of songs of New South Wales, the words of which cannot be related to Awabakal, eleven pages of “Specimens of the Language of the Aborigines of New South Wales to the Northward of Sydney” with translations in a language closely resembling Awabakal, possibly a dialect of it, and a final four pages of vocabulary from Port Essington and Port Raffles, in the Northern Territory. Different pages are written in different hands, several in a style of handwriting unlike Threlkeld’s. If the Awabakal-like pages were not written by Threlkeld, who other than he would have had the knowledge to produce them? Perhaps one or other of his children might have been responsible.

Analysing the Threlkeld work corpus

Virtually every phrase and sentence of Threlkeld’s works have been analysed by Your Amateur Researcher in a 5-line pattern, illustrated below and in the frames of first pages in the summary table following.

The 5-line analysis of each phrase or sentence consists of the following:

1. Threlkeld’s translation into Awabakal (green background to the text)

2. Threlkeld’s translation into Awabakal, respelt (green type)

3. The original English (grey background)

4. Word-for-word translation of line 1 above (yellow background)

5. Back-translation of line 1, in stilted English, to follow the word order (pale blue background)

Commentary “patches” are included throughout the analysis, which it is hoped might assist any reader. Sometimes these comment on the quality of Threlkeld’s translations, even occasionally suggesting revisions. The patches are mostly self-explanatory. Some are repeated, to save the reader from having to search back for the comment to the first time a particular matter arose. Sometimes they reflect Your Amateur Researcher’s thoughts about the topic concerned.

In the following table of the analyses of Threlkeld’s works only the first frame is shown for each publication. A note at the top of each shows how many such frames follow, there being nearly 2000 in the case of St Luke’s gospel.

Internet links are provided for each publication, both to the location in the Languages of Australia website (aboriginallanguages.com) where the analysis is to be found, as well as to where the original document can be found on the internet.

Orthography and Orthoepy

Total frames: 20

Website

https://www.aboriginallanguages.com/threlkeld/threlkeldsentences

Internet

https://hunterlivinghistories.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/1825-Threlkeld-Orthography.pdf

Specimens of a Dialect

Total frames: 107

Website

https://www.aboriginallanguages.com/threlkeld/threlkeldsentences

Internet

https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-1711000/view? partId=nla.obj-1711450#page/n4/mode/1up

Gospel of St Luke

Total frames: 1934

Website

https://www.aboriginallanguages.com/threlkeld/threlkeldluke

Internet

https://kura.aucklandlibraries.govt.nz/digital/collection/manuscripts/id/13128

Use the arrows to the right and left of the Gospel illustration to turn the pages.

Exercise book

Total frames: 39

Website

https://www.aboriginallanguages.com/threlkeld/threlkeldsentences

Internet

NO INTERNET COPY could be found June 2025

Selection of Prayers

Total frames: 169

Website

https://www.aboriginallanguages.com/threlkeld/threlkeldprayers

Internet

https://livinghistories.newcastle.edu.au/nodes/view/56289#idx57126

Illustrative Sentences in An Australian Grammar (1834)

Total frames: 110

Website

https://www.aboriginallanguages.com/threlkeld/threlkeldsentences

Internet

https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-115132947/view? partId=nla.obj-484935868#page/n119/mode/1up

Spelling Book

Total frames: 51

Website

https://www.aboriginallanguages.com/threlkeld/threlkeldsentences

Internet

https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-52763467/view? partId=nla.obj-88016559#page/n4/mode/1up

Gospel of St Mark

Total frames: 1194

Website

https://www.aboriginallanguages.com/threlkeld/threlkeldmark

Internet

Gospel of St Matthew

Total frames: 154

Website

https://www.aboriginallanguages.com/threlkeld/threlkeldmatthew

Internet

NO INTERNET COPY could be found June 2025

Key

Total frames: 102

Website

https://www.aboriginallanguages.com/threlkeld/threlkeldsentences

Internet

https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-222915774/view? partId=nla.obj-222917588#page/n4/mode/1up

Karree list Specimens of the Language of the Aborigines of New South Wales to the northwards of Sydney

Total frames: 84

Website

https://www.aboriginallanguages.com/threlkeld/threlkeldsentences

Internet

https://collection.sl.nsw.gov.au/record/9Bv7zaD9/2NboLAzb7zdQP

Jeremy Steele

6 June 2025

Comments